First the bad news: 50% of humanity are born pessimists. Pessimists tend to catastrophise problems. Moreover, pessimists always find exactly one culprit for all the ills of this world: themselves. In the Stone Age, when homo sapiens still had to fight for survival every day, pessimism was not a bad idea at all. It simply paid to be extremely paranoid. Those who did not always immediately suspect the worst and prepare for it were soon history. Whether poisonous spiders, snakes, sabre-toothed tigers or simply a horde of hungry, club-wielding Neanderthals - death and destruction lurked under every stone and around every corner. Those who were not extremely cautious and constantly on the lookout for death and the devil under such circumstances simply no longer existed after a very short time. And so it is that those who had many fears and worries survived and passed on their genes to us.

Physiologically, we are not very different from Stone Age people. However, what was very useful in an extremely hostile environment, our pain and fear memory, turns into a curse in the modern world. Depression and anxiety disorders, as well as countless other degenerative diseases that are ultimately autoimmunological, are now responsible for much of the cost in our health care system. Of course, people still die in road accidents or from other "natural" causes of death. However, by far the largest part, not only of the deaths but above all of the unimaginable amount of "silent infirmity" and miserable because powerless suffering of many people, is no longer caused by a hostile environment but by a corrupted "inner milieu". In other words, in the ability for self-regulation, which is currently still largely unused but can be learned.

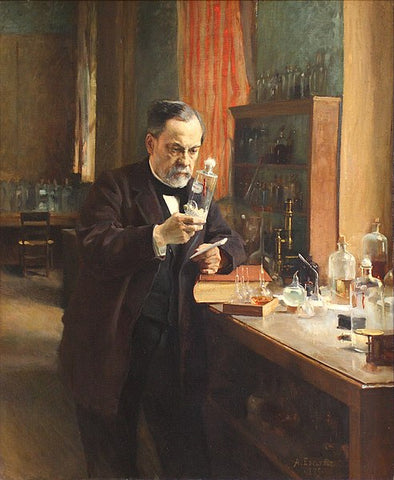

In this painting by Albert Edelfelt, Louis Pasteur looks at a bottle in which the dried spinal cord of a rabid rabbit hangs by a thread over a desiccant. Pasteur is the founder of the vaccine industry. - Is it possible that the vaccine debate is missing the point? Vaccinations may benefit or harm humans. What is much more interesting is what the next evolutionary step of the human being looks like. The more highly developed a being is, the greater its capacity for self-regulation. This can be exemplified by heat regulation. While plants, fungi, fish, amphibians and reptiles are still dependent on sunlight for their metabolism, birds and mammals can regulate their own body heat largely independently of the ambient temperature. Could the same be true for our immune system? There is a lot to be said for it! An extreme example of this thesis is the "Iceman" Wim Hof - who seems to be immune to any form of viral infection and also successfully teaches this trait.

In ancient times, it was believed that human health - once apart from the "will of the gods" - essentially depended on the interaction of different bodily fluids. In Eastern health teachings, we still find similar ideas of a universal life energy called "prana", "ki" or "chi". Even in the late 19th century, the "father of microbiology" and developer of the first vaccines, Louis Pasteur (1822 - 1895), personally believed in a vital life force that could not be explained in purely physical terms. The term "milieu interior" goes back to Pasteur's contemporary Claude Bernard (1813 - 1878) and refers to the 60-70% fluid of the human body, which today is called the "extracellular matrix". Walter Cannon (1871 - 1945) took up Bernard's concept of milieu and developed the concept of "homeostasis" from it. Norbert Wiener (1894 - 1964) in turn transferred Cannon's terms to cybernetics. And so the diffuse idea of an obscure "life force" of earlier centuries entered modern natural science as the "capacity for self-regulation", where it is still considered one of the primary properties of all living systems.

Now the good news: optimism can be learned. The "father of positive psychology" - not to be confused with the demonstrably harmful "positive thinking" - Martin Seligman believes that an "optimistic explanatory style" can be systematically learned, which in turn has a positive effect on the "milieu". In the 1950s, Seligman intensively studied the phenomenon of "learned helplessness". Animals that were arbitrarily and repeatedly inflicted with pain without being able to actively do anything about it soon became apathetic and resigned. The animals remained inactive and lethargic in their cages even when the environmental conditions simulated in the laboratory had long since changed again. Once conditioned, the laboratory animals remained trapped in the impotent behavioural pattern of "learned helplessness" until their miserable end. Their immune system was - we can assume - lastingly weakened. In this way, they resemble in some respects the genetically predisposed pessimists among us, who in an incredibly safe, modern environment still behave like extremely paranoid - and unfortunately then often violent - Stone Age people.

An optimistic and a pessimistic explanation for an experience that is assessed as negative differ fundamentally in three respects according to Seligman's research: 1. the probable temporal duration , 2. the extent of the damage done and 3. the derivation of the supposed causes. Let us relate this to the current Corona crisis for better illustration. The pessimist thinks - unconsciously - that this crisis will last "for a very long time" and will change the world "forever" - to the negative, of course (1). These negative changes will affect "all areas of life" (2). The blame for the crisis can be placed on nature, the government, the Chinese, the pharmaceutical cartel, "dark forces", extraterrestrials or Bill Gates himself. In any case, there is a sinister plan behind it that wants to deprive me of my personal freedoms, dearly won through countless heroic acts of sacrifice (3). The optimist, on the other hand, thinks that the crisis will be over (1) in the foreseeable future and then hardly anyone will remember it (2). The optimist - who does not consider himself the centre of world events, like the pessimist - practices the attitude of pronoia: the completely unfounded initial suspicion - of an ethical decision - that the universe might ultimately mean well with him. (3).

The two styles of explanation can also be applied to positive experiences. Suppose - purely theoretically, of course - someone wrote a blog post and then came to the conclusion that they had achieved something great. The pessimist now thinks that this must be a (1), completely isolated (2)coincidence (3) lasting only a short time. The person affected by the frighteningly widespread Impostor Syndrome thinks deep down that everything good that happens to him must basically be based on an error, which will be discovered sooner or later. The optimist, on the other hand, thinks that this will be just the beginning (1)of a long series of successful experiences in his life (2)which will ultimately be based on what a horny guy (3)he is himself.

The question of the "right" explanatory style cannot be decided "objectively". Just like all ethical decisions, it ultimately remains a question of faith. Faith is a decision about what I "faithfully base my actions on". If "I" - as both Buddha and modern brain research suggest - am only a habit, then I can, with much patience and practice, also learn to be an optimist and thereby modulate or self-regulate my immune system naturally and sustainably.